Health of your ACD

The Australian Cattle Dog like most breeds have hereditary and congenital problems which the new owner should be aware exist and should discuss with the breeder prior to purchase.

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA)

Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) refers to a group of inherited diseases that cause loss of sight in many dog breeds. Most forms of PRA are believed to be inherited as simple Mendelian recessives. They differ in their age of onset and histology. Progressive Rod/Cone Degeneration (prcd) is the form of PRA found in the Australian Cattle Dog (ACD) and in the Australian Stumpy Tail Cattle Dog (ASTCD).

Prcd is known to have caused blindness in Cattle Dogs as young as 3 years old. Age of onset is, however, variable. Some Cattle Dogs do not develop clinical signs of the disease until they are 6 or 7 years old, or even older.

Prcd has been known in ACDs population from early in the breed’s history. Old stories have been handed down about “moon-blindness” or “night-blindness” and inability to see in subdued light. These observations are often a sign of prcd. More recently, it become evident that the incidence of prcd was alarmingly high. Because prcd is commonly late in onset, affected animals may parent litters before the disease is diagnosed.

Wooleston Blue Jack, and his ancestors Little Logic and Logic Return are behind all modern ACDs. Pedigree study suggests that the popularity of this lineage, and the genetic convergence on it, may have contributed to increased incidence of prcd. It is probable that Little Logic carried the disease. For example: Glennie Blue Gem, whelped in 1964, was closely line bred to Little Logic. Her blindness is thought to have been the result of prcd.

Prcd is inherited as an autosomal recessive. This means that an affected dog must have inherited the prcd gene from both parents. A dog that inherits the prcd gene from one parent and the healthy gene from the other will not develop the disease, but can pass the prcd gene on to its offspring. Such a dog is known as a carrier for prcd. A dog which has no copies of the prcd gene can’t (obviously) pass on the disease – such a dog is known as clear for prcd.

Prcd in ACDs attracted the interest of Dr Greg Acland, an Australian veterinary ophthalmologist holding research and academic positions in the USA. In 1996, Dr Acland collected blood samples from over 100 ACDs in the United Kingdom and Netherlands for initial study. Blood samples from ACDs in North America and Australia later enlarged the collection. Dr Acland’s research, carried out at Cornell University, was successful, in 2002, in proving a DNA test that can (a) identify prcd affected ACDs before the disease becomes clinically evident, (b) can determine whether a dog carries the disease (even though it is itself unaffected), and (c) can identify dogs that are completely clear of the disease. More information can be found at http://www.optigen.com/.

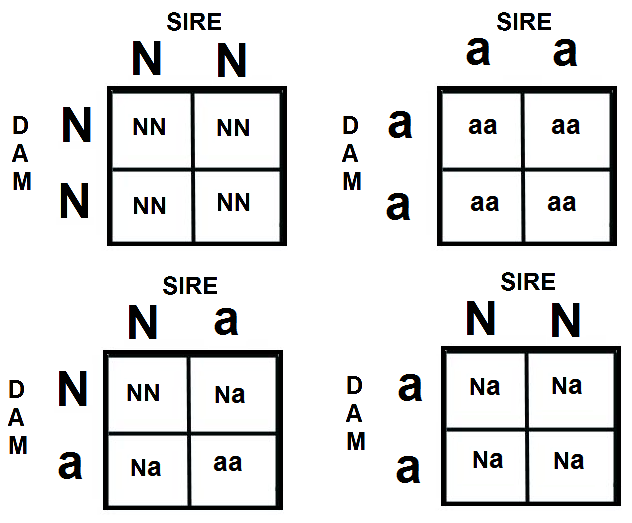

One way to predict breeding risks for this sort of disease can be calculated using the Punnett Square:

- If both parents are non-carriers/clear (N/N) then all of the puppies will be clear.

- If one parent is a carrier (N/a) and one is non-carrier/clear(N/N) each puppy has a 50% chance of being non-carriers/clear and a 50% chance of being a carrier.

- If both parents are carriers (N/a) each puppy has a 25% chance of being non-carrier/clear (N/N), 50% chance of being a carrier (N/a), and 25% chance of being affected and carrier (a/a)

- If one parent is non-carrier/clear (N/N) and one parent is affected (a/a) then all puppies will be carriers (N/a)

- If one parent is a carrier (N/a) and one is an affected carrier (a/a) each puppy has a 50% chance of being a carrier (N/a) and 50% chance of being affected/carrier (a/a)

- If both parents are affected/carriers (a/a) then all puppies will be affected/carriers (a/a)

Primary Lens Luxation (PLL)

The lens is held in its normal position behind the iris and pupil by tiny strands called "zonules". Disruption of the zonules can cause the lens to move out of its normal position (luxate). When a lens is only partially held by some zonules, it is referred to as a subluxated lens. When a lens is no longer held by any zonules, it is called a luxated lens.

Two general categories of lens luxation are defined according to whether or not the luxation was the first eye problem (primary lens luxation) or whether it was caused by another eye condition (secondary lens luxation). Primary lens luxation is seen more commonly in certain breeds (e.g. Jack Russell Terriers, Miniature Fox Terriers, Tenterfield Terriers and Cattle Dogs) where the defective lens zonules weaken and break over time. Trauma to the eye or head can also cause lens luxation, although it is not usually the primary cause. Trauma severe enough to cause lens luxation usually also causes other obvious eye problems.

Lens luxation can be secondary to other eye diseases such as glaucoma or uveitis. Elevated pressure inside the eye (glaucoma) or inflammation inside the eye (uveitis) can cause the zonules to weaken and the lens breaks free. Interestingly, a luxated lens can also cause glaucoma. Sometimes when we see a patient with multiple eye problems for the first time, it is difficult to tell which problem came first: the luxated lens or another eye condition!

Treatment of a luxated lens depends on the general health of the eye, the position of the lens, and whether or not the patient can still see out of the affected eye. If the lens is loose but is still behind the iris, we sometimes use medications which constrict the pupil in order to trap the lens in its proper position. If the lens has moved in front of the iris, then surgery may be recommended to remove the lens.

Prior to the surgical removal of a luxated lens (lensectomy), preoperative electronic testing of the back of the eye must be done to make sure the retina is working properly. This is to ensure the patient will be able to see after surgery. Lensectomy is done under general anaesthesia with the use of an operating microscope. An incision is made in the edge of the eye and the lens is removed using a small spoon shaped device called a lens loop, or a probe with a frozen tip is inserted into the eye to capture the lens. The lens adheres to the end of the probe in the same way your tongue would stick to a frozen lamp post in the winter! The surgeon then pulls out the lens in one piece. The corneal incision is sutured closed.

Responsible breeders will have their dogs DNA tested and this identify their dog as belonging to one of three categories:

CLEAR: these dogs have two normal copies of DNA. Our research has demonstrated clear dogs will not develop PLL as a result of the mutation we are testing for, although we cannot exclude the possibility they might develop PLL due to other causes, such as trauma or the effects of other, unidentified mutations.

CARRIER: these dogs have one copy of the mutation and one normal copy of DNA. Our research has demonstrated that carriers from some breeds have a very low risk of developing PLL. The majority of carriers do not develop PLL during their lives but a small percentage do. This has been particularly noted for the Miniature Bull Terrier during our study and is also suggestive in the Lancashire Heeler. For Tibetan Terriers our study did not show any evidence to suggest that carriers will develop PLL. For the Miniature Bull Terrier we estimate that between 2% and 20% of carriers will develop the condition, although we believe the true percentage is nearer to 2% than 20%.

We do not currently know why some carriers develop the condition whereas the majority do not, and we advise that all carriers have their eyes examined by a veterinary ophthalmologist every 6- 12 months, from the age of 2, throughout their entire lives.

GENETICALLY AFFECTED: these dogs have two copies of the mutation and will almost certainly develop PLL during their lifetime. We advise that all genetically affected dogs have their eyes examined by a veterinary ophthalmologist every 6 months, from the age of 18 months, so the clinical signs of PLL are detected as early as possible.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Deafness

Studies of congenital deafness in the dog are limited although those breeds to date with the highest prevalence include the Australian Cattle Dog, Australian Shepherd, Bull Terrier, Catahoula, Dalmatian, English Cocker Spaniel, English Setter and West Highland White Terrier.

Inherited congenital sensorineural deafness is usually, but not always associated with pigmentation genes responsible for white in the coat, but, as the Dalmatian is influential in the overall makeup of the Australian Cattle Dog, the breed is unfortunately plagued with this problem.

Through extensive research it has been established that deafness does not develop in dogs until the first few weeks of life, with normal development occurring to that point. Studies have shown that Australian Cattle Dogs do not go deaf until weeks 3-4 weeks after birth. The histologic pattern that occurs in most dogs breeds is known as cochleo-saccular, or Scheibe, type of end organ degeneration.

Since the ear canal does not open until approximately 14 days in dogs, and deaf puppies cue off the responses of litter mates, and it is not uncommon for deafness to go unrecognized for many weeks. In some breeds, deaf puppies will display more aggressive play with litter mates because they do not hear cries of pain, but deaf puppies after weaning will not waken at feeding times unless physically shaken.

Assessment of the presence of auditory function requires a simple test known as brainstem auditory evoked response or BAER as it is commonly known. In this test a computer based system detects electrical activity in the cochlea and auditory pathways in the brain in much the same way that an antenna detects radio or TV signals.

BAERCOM units are readily available throughout Australia. Therefore there is no excuse for a breeder not to have a litter of pups tested prior to sale.

Deaf dogs have special needs and dedicated, experienced trainers. Unilateral deafness where the dog has full hearing in one ear only is a easier problem to manage and these dogs make ideal pets with the owners often unable to detect any impairment. Some dogs with unilateral deafness will show a directional deficit and may not immediately reactive to your presence if sleeping soundly with the good ear on the ground. However, there is no evidence to discourage breeding from unilaterally deaf dogs, although preference to breeding with full hearing dogs will with the cooperation of all breeders eventually prevent further affected dogs and the ultimate increase in the prevalence of the disorder.

Read more about deafness at at www.lsu.edu/deafness/deaf.htm. Support for deaf dog owners is widely available, as it is a common problem in many breeds.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Hip Dysplasia (HD)

Hip Dysplasia appears in many breeds of dogs. In some breeds it is the most common cause of osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease. The term dysplasia is a developmental condition that results in abnormal looseness or laxity of the hip joints.

The signs of HD vary from decreased exercise tolerance to severe crippling although some dogs may never shows signs of dysplasia and generally remain very fit and active. Even though a large percentage of Australian Cattle Dogs today do not work stock as such, they channel their energy and intelligence into other activities including obedience, agility, tracking, showing and being the active family member therefore the exercise diminishes the affects of this common and often crippling disease.

Any diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia must be made via expert radiographic diagnosis. This involves taking x-rays of the joint and typically sending the film to organizations that will evaluate, register and certify the dog. You cannot make a reliable diagnosis of HD on the basis of external symptoms such as lameness or gait.

More information can be found at http://www.hipdysplasiaindogs.com/

Normal hips Dysplastic hips

Osteochondrosis of the shoulder (OCD)

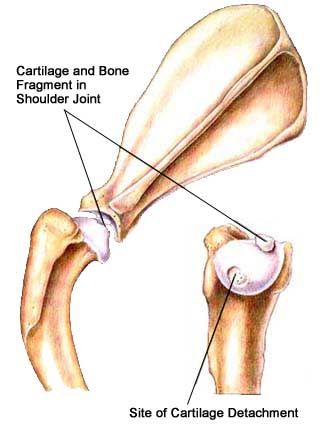

Osteochondrosis occurs commonly in the shoulders of immature, large, and giant-breed dogs. The lesion usually appears on the caudal (back) surface of the humeral head. Osteochondrosis begins with a failure of immature cartilage to form bone in the humeral head. This failure leads to abnormal cartilage thickening. Increased cartilage thickness may result in malnourished cartilage cells that die.

Loss of these cartilage cells deep in the cartilage layers leads to formation of a defect at the junction between cartilage and bone. Subsequently, normal daily activity may cause fissures in the cartilage that eventually communicate with the joint, forming a cartilage flap (Figure 3). It is with the formation of a flap that osteochondrosis becomes osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). OCD is the form of osteochondrosis that is associated with pain and dysfunction. In some cases, the resulting flap occupies as much as half the humeral head. The cartilage flap may completely detach from the underlying bone and become lodged in the back of the joint pouch. Free cartilage flaps can lodge in joints and may increase in size with calcification becoming "joint mice” which can be seen on radiographs.

The causes of OCD are multifactorial with genetic and nutritional interactions thought to be the central factors. Risk factors for OCD may include:

- Breed genetics (Polygenic trait)

- Age

- Gender

- Anatomic abnormalities

- Rapid growth

- Nutrient excesses (primarily protein, energy, calcium, and phosphorus)

- Trauma

Due to the high frequency of occurrence within certain breeds of dogs and within certain bloodlines, heredity may be an important factor. Males are more commonly affected than females.

Clinical signs often develop when the dog is between four and eight months of age. Dogs usually begin limping on one of their forelimbs. In many cases, a gradual onset of lameness improves after rest and worsens after exercise. Although your pet may be lame on only one leg, this condition may be present in the opposite leg too.

Elbow Dysplasis

Canine elbow dysplasia (ED) is a disease of the elbows of dogs caused by growth disturbances in the elbow joint. There are a number of theories as to the exact cause of the disease that include defects in cartilage growth, trauma, genetics, exercise, diet and so on.

It is likely that a combination of these factors leads to a mismatch of growth between the two bones in the fore leg located between the elbow and the wrist (radius and ulna). If the radius grows more slowly than the ulna it becomes shorter leading to increased pressure on the medial coronoid process of the ulna. This in turn can cause damage to the cartilage in joint and even fracture of the tip of the coronoid process, which damages the medial compartment (side closest to the body) of the joint. Less commonly, if the ulna grows too slowly then the radius pushes the upper arm bone (humerus) against the anconeal process, which can then lead to failure of the anconeal process to attach to the ulna at maturity. It is believed that the mismatch in growth between the radius and ulna may sometimes only occur during a puppy’s growth, but it may also persist when the pup has finished growing.

Luxating Patella

There are many types and degrees of patella luxation. The patella or kneecap can luxate or dislocate medially which is towards the body midline or laterally which is away from the midline and can be traumatic or congenital in origin. The problem has been evident in Australian Cattle Dogs for some time with the breed suffering from lateral luxation in most cases diagnosed.

Surgical correction is not usually necessary unless the dogs shows symptoms such as pain or gait abnormalities. The condition can be easily diagnosed by your veterinarian and a simple check of the patella can be performed by your veterinarian to see if the dog is predisposed to the condition. In Australian Cattle Dogs luxating patellas has shown to be an inheritable problem, and as such a dog that possesses this problem should not be bred as the possibility of it’s progeny inheriting the condition is high. Also studies show that in about 50% of cases treated surgically the dog demonstrates reoccurring patellar luxation in as short a time as 1 year. ore information can be found at www.vetsurgerycentral.com/patella.htm

Degenerative Myelopathy (DM)

Degenerative Myelopathy (DM) is a progressive neurological disorder that affects the spinal cord of dogs. Dogs that have inherited two defective copies will experience a breakdown of the cells responsible for sending and receiving signals from the brain, resulting in neurological symptoms.

The disease often begins with an unsteady gait, and the dog may wobble when they attempt to walk. As the disease progresses, the dog's hind legs will weaken and eventually the dog will be unable to walk at all. Degenerative Myelopathy moves up the body, so if the disease is allowed to progress, the dog will eventually be unable to hold his bladder and will lose normal function in its front legs. Fortunately, there is no direct pain associated with Degenerative Myelopathy.

The onset of Degenerative Myelopathy generally occurs later in life starting at an average age of about 10 years. However, some dogs may begin experiencing symptoms much earlier. A percentage of dogs that have inherited two copies of the mutation will not experience symptoms at all. Thus, this disease is not completely penetrant, meaning that while a dog with the mutation is likely to develop Degenerative Myelopathy, the disease does not affect every dog that has the genotype.

Contact Details

Kombinalong Kennels

NSW Australia

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 0419787375

ABN 99 209 925 507